-

News & Events

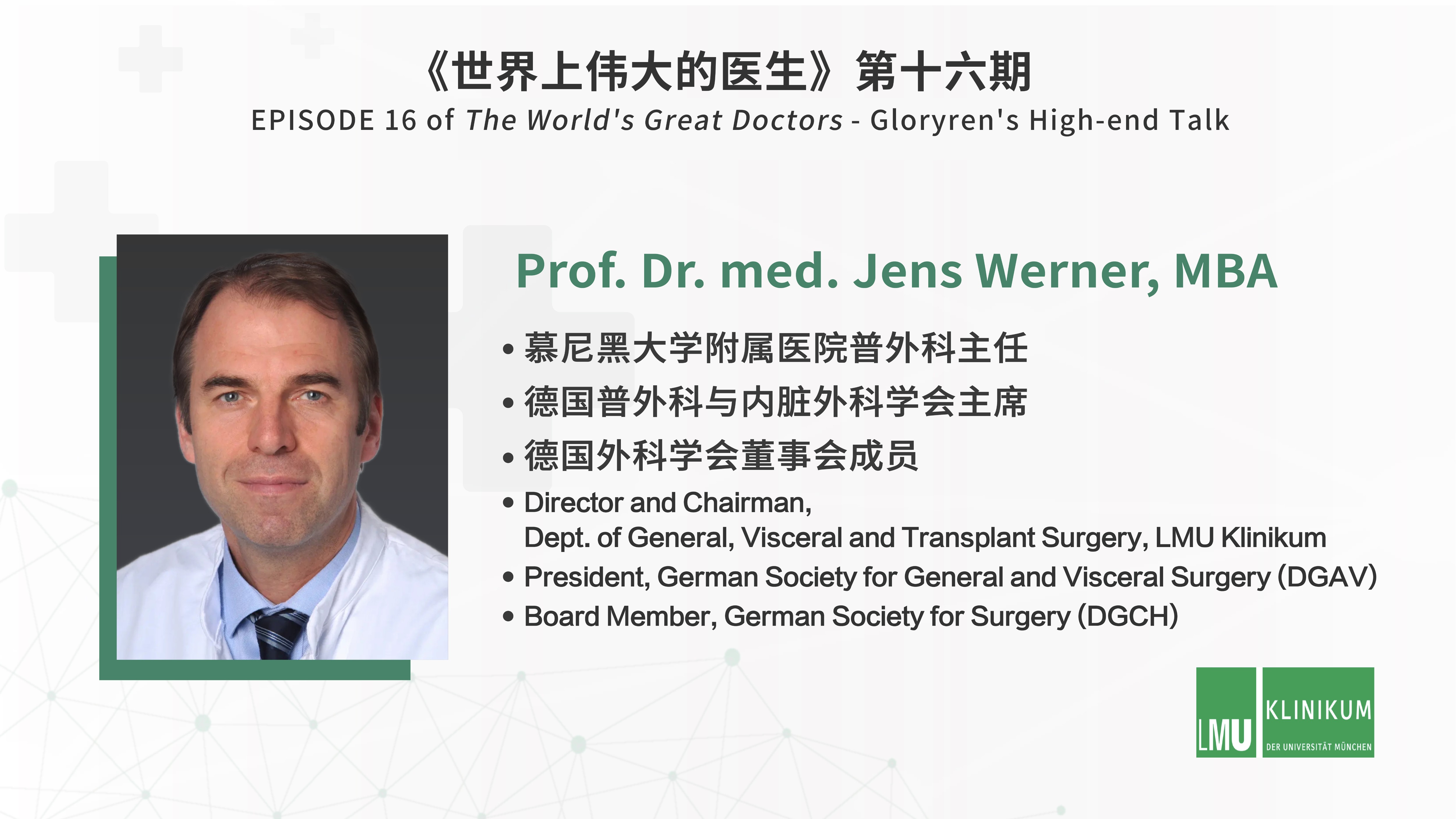

For EPISODE 16 of the World’s Great Doctors, it is our great honor to have Prof. Jens Werner as our distinguished guest, who is the Director and Chairman of General, Visceral and Transplant Surgery at the prestigious University Hospital of Munich and the President of the German Society for General and Visceral Surgery (DGAV).

Over the last decade, Prof. Werner and his team have been striving in establishing a clinic treating full spectrum of relevant diseases with sub-specialties. So far, it has been certified as Excellence Centers for pancreatic surgery, liver surgery and surgical coloproctology by the German Society for General and Visceral Surgery (DGAV) and has been Visceral Oncology Center, Pancreatic Cancer Center, Liver Cancer Center, Colorectal Cancer Center and Gastric Cancer Center by German Cancer Society (DKG).

1. Why did you decide to pursue a career in medicine and why, in particular, did you decide to specialize in General and Visceral Surgery?

Actually, I wanted to become a medical doctor and a surgeon my whole life. Probably it’s helper syndrome - I like to help people. My role models were some friends of my parents.

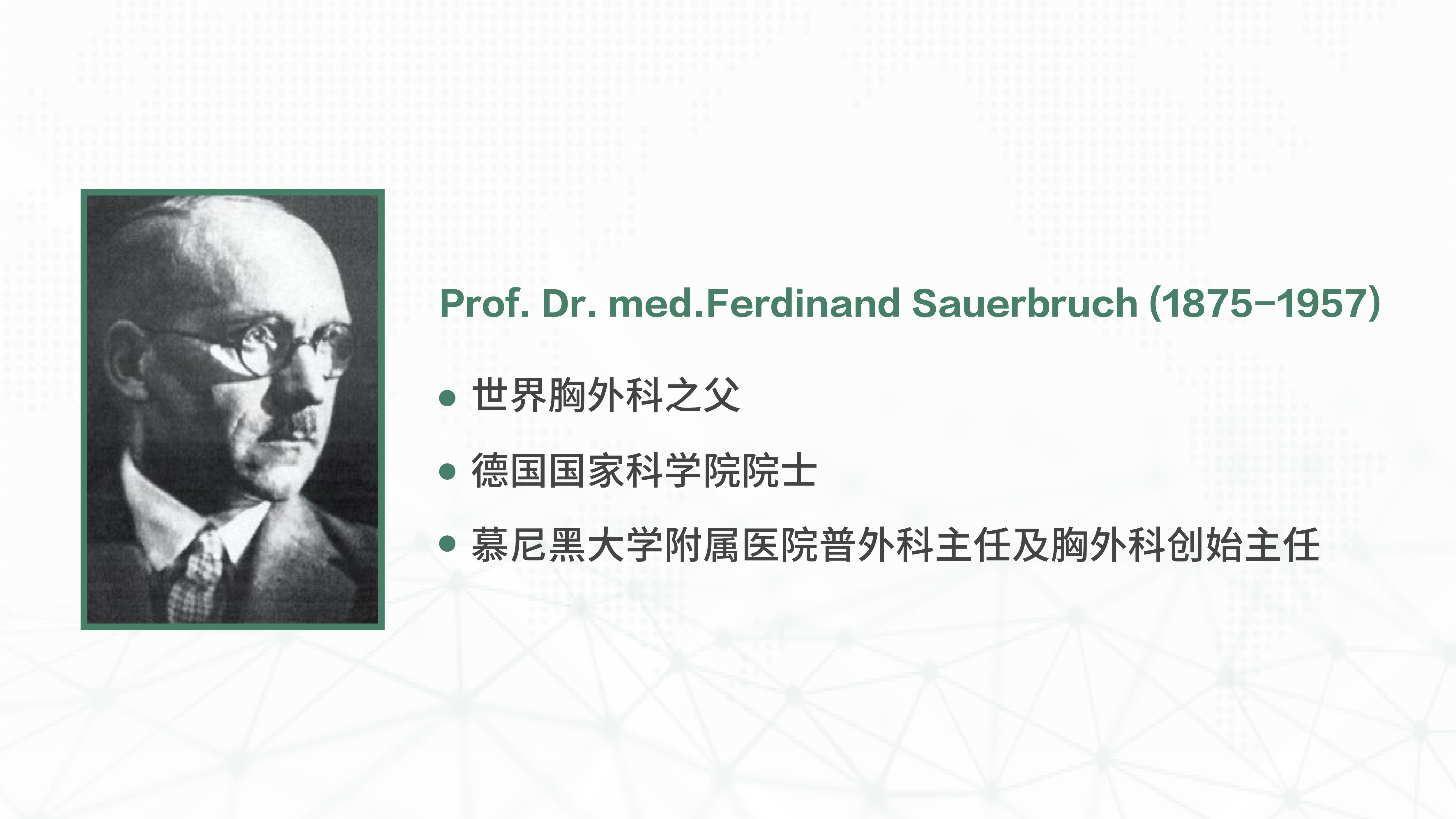

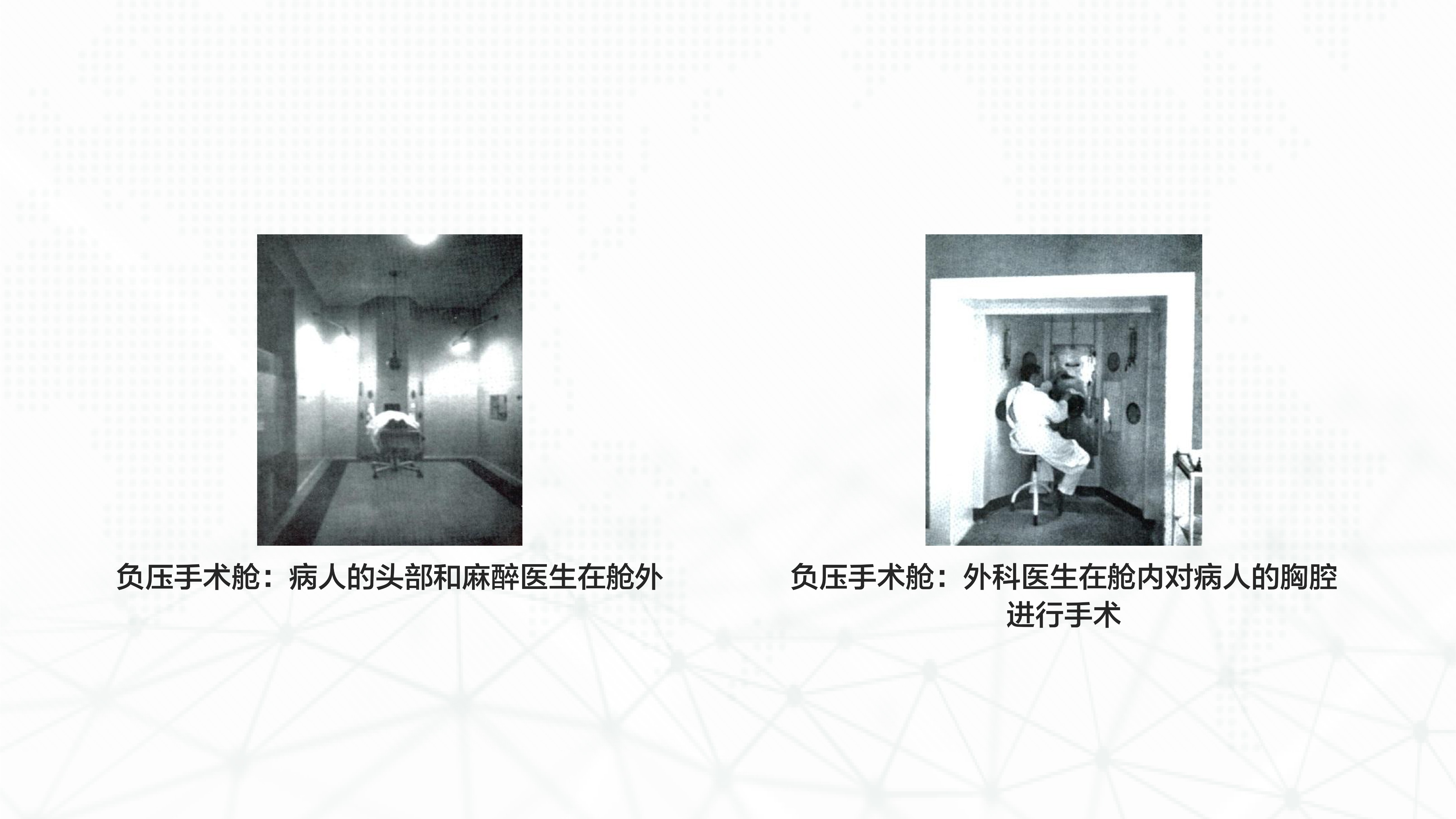

And in my hometown, we had a very famous surgeon called Ferdinand Sauerbruch, who invented a forearm prosthesis and a vacuum chamber that surgeons could actually work and operate on the lung. By accident, he actually was a predecessor of my position here in Munich in the early twenties of the last century. Coincidentally, he was actually born in my hometown so I knew about him much earlier, and I read some stories (about him). This was the idea (of being a surgeon).

And in my hometown, we had a very famous surgeon called Ferdinand Sauerbruch, who invented a forearm prosthesis and a vacuum chamber that surgeons could actually work and operate on the lung. By accident, he actually was a predecessor of my position here in Munich in the early twenties of the last century. Coincidentally, he was actually born in my hometown so I knew about him much earlier, and I read some stories (about him). This was the idea (of being a surgeon).

Then actually I wanted to become an orthopedics and traumatology doctor first, working on the spine. But when I was in medical school, I visited those traumatologists and I found it too mechanical, while I wanted to focus on the diseases and the biology of them. So I ended up with general surgery. And to become a general surgeon means you are a gastroenterologist, endocrinologist, oncologist who can operate. It's a combination of being a physician and a surgeon, so it's a great job.

That's actually how I entered general and visceral surgery, which was a development.

2. Who have been you greatest influences? What have they taught you and how have they inspired you?

Of course, my greatest influences are my parents, (especially) my father and it's mainly about the work ethics. He taught me to focus and to work hard.

But then I had mainly three teachers.

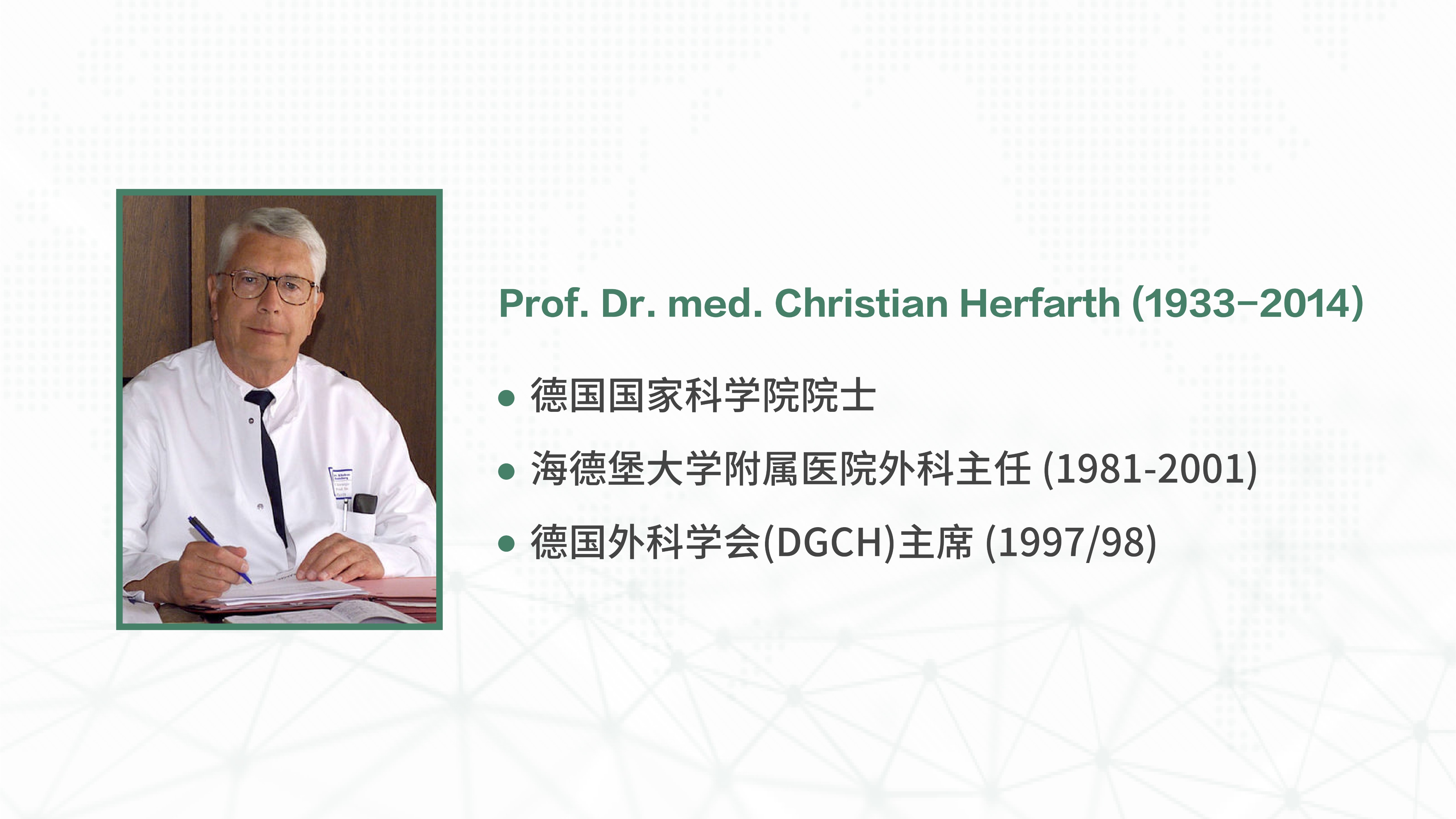

The first is Professor Herfarth, my first Chief of Surgery in Heidelberg. He was mainly focusing on colorectal surgery and transplant surgery. His main focus was always that we need to care for your patient first, so that's the most important one and I really learned the basics of how to handle patients and how to take care of them and how to do surgery as well.

My second teacher in surgery was Professor Büchler in Heidelberg. He was my second Chief there after Professor Herfarth has retired. He taught me about pancreatic surgery, hepatobiliary surgery, but he also focuses more on organizing a department, managing medical departments. In the year 2010, because a lot of things changed over the time and it's not only enough to perform good surgery, but you need to actually handle the whole organization of your clinic and your department. Professor Büchler is really someone who taught me that and we all studied MBA. And the other great thing about Professor Büchler is that he was excellent in motivating people. That's also something you need to learn - how do you motivate people to work hard and to actually reach their best. This is something you can do by nature, but you can also learn this. This is what I learned from Professor Büchler.

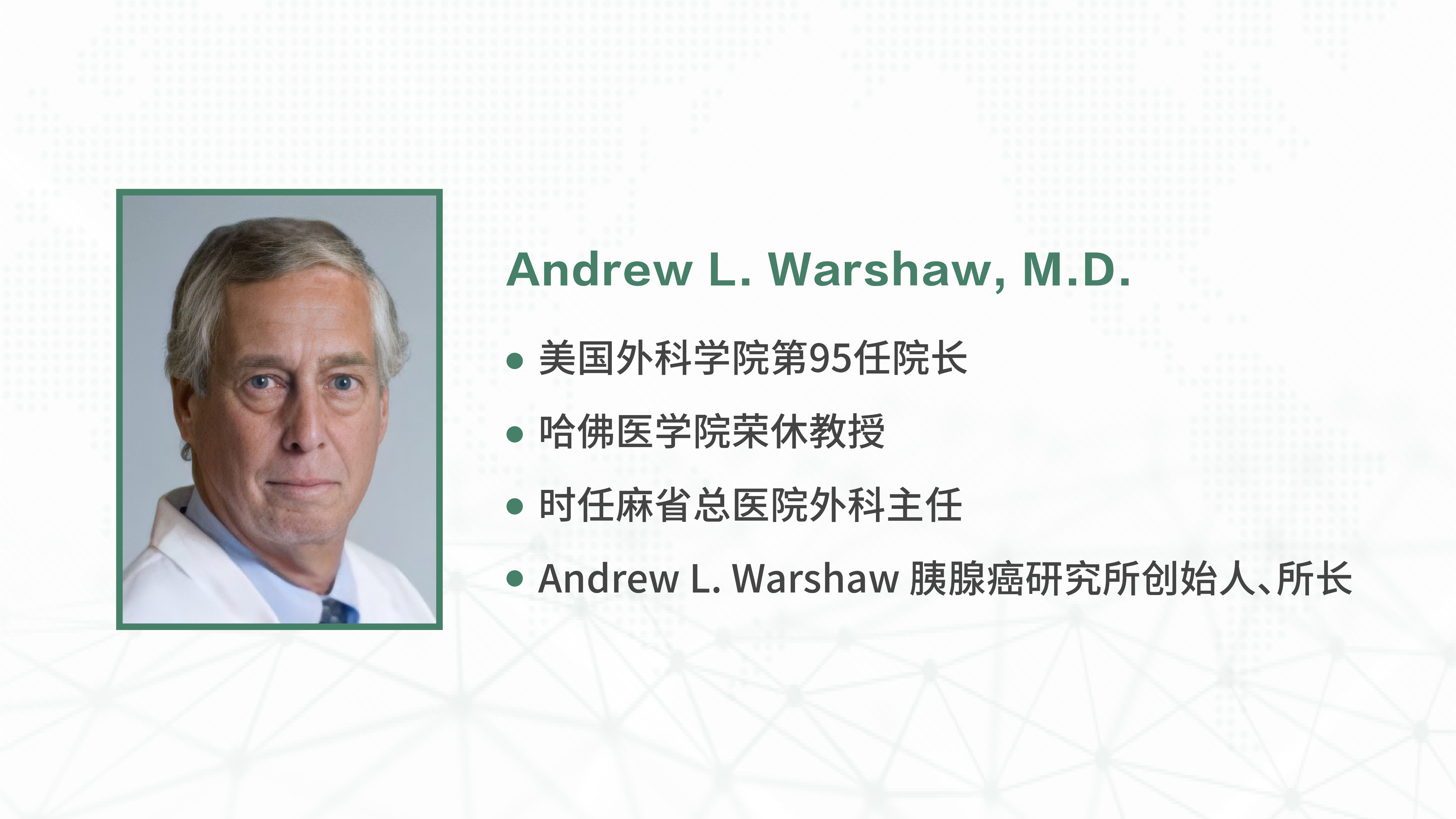

And then my third teacher was Professor Warshaw, who was the Head of the Department of Surgery at MGH in Boston and I've done a lot of research there and also learned how to organize research and a hospital unit as well.

You mentioned that Professor Herfarth inspired you that patient care is the priority for the surgeons. And patient care is not only about medical needs but also emotional support. But currently in many large Grade Three Class A hospitals in China, many doctors do not show enough respect to the patien ts or treat them nicely due to the large amount of patients. What’s your thought on this?

Yeah, probably you're right. The problem is that once you have so many patients to care about, you don't care about the patient himself or herself anymore, but you may be just focusing on the workload, or else you will be overwhelmed. Here in Germany, I think, you need to be with your patient because it could be your mother, it could be your father, this is a way to approach, so you need to help people in the hospital. It's the same when you find someone looking for the right direction in the hospital or on the street, you will help them and give them the right direction. It's a matter of how to communicate within a society. It is something you can actually observe in Germany as well, also outside the hospital - the bigger the city is, could less friendly the people be, because they are in stress. You can see this when they drive a car, they will always try to be over the traffic jam first, and nobody cares about the others. But in a smaller village, people care about others because they know each other and they know that they need to rely on each other. It's similar in a hospital, if you don't care about customers, the patients, or the person who is with you, things won't be okay. Patients need to trust you. I am convinced that (if so) your results will be much better as well because part of the healing is not the mechanical doing but it's also that you need to convince people that you're the right person to do this job. Otherwise, they are in stress and may develop complications and everything. So I think it's something you need to do from your heart, and you need to learn.

3. Many patients feedback that they feel anonymous when receiving treatment at large hospitals - the diagnosis and treatment are state-of-art and top-class, but the emotional support and care are not adequate. Has this ever happened in your clinic? How do you solve/prevent this problem?

It's a bias that is present in the population everywhere, I think. It's probably not only true for hospitals but for any kind of business. For example, for the bookshop, you have a small corner shop and you have some big chains, and for bakeries, butchers or supermarkets... If you enter a bigger business you are not realized as a person immediately, so it's your (the Chief’s) job to make an environment where people and patients feel welcome. This is definitely more difficult in a bigger hospital or bigger business. The only solution for this is that, you personally try to be a role model for all your surgeons and that they follow what you do. If you treat everybody well and treat your coworkers well, as well as the patients, then everybody might see that this is a good way to act. But you won't be able to influence everybody. This is true in big business as well as in small businesses and also in hospitals, the point is to select a way how to communicate with people, and then everything will be fine.

And in Munich, we have the problem as well because we have two sites, and the site in the inner city is smaller. People like to go there because it's not only because of the communication, it's also because people may think if they go to the small hospital, they are not so ill, but if they go to the big hospital, it's really serious. In the past, people in Munich only entered the hospital in Grosshadern when they were really sick. But then we try to change all this. It's a matter of activity to communicate that a big hospital is also able to care about the personal needs of the patients, but it's a big challenge.

4. You have been leading the Clinic for General, Visceral and Transplant Surgery for around ten years. What was the biggest challenge during the last decade? And as the Chief, what’s you plan for the next decade?

Over the last ten years I really tried to establish a good clinic with all the sub-specialties. So far, we have been certified for excellence in many fields. My job was to come up with the right surgeons and the right organizational structure in the hospital and to develop new techniques here in the LMU.

It's always difficult to build something, but the real challenge is to keep something at a high level. So this will be the task of the next years.

I also think that in Germany we have a lot of great hospitals and big hospitals like ours, but the main work in the future will be to provide the excellent care to the rural areas as well. So you need to come up with networks of smaller community hospitals with bigger universities and try to centralize the care for patients who normally don't go to the big cities and to the big hospitals.

As for the biggest challenge over the past decade, it was the Covid-19 pandemic two years ago. Now it's not a problem anymore and it’s getting more normal, but two years ago that was a big challenge.

5. The field of General and Visceral Surgery has a wide spectrum and many diseases should be treated jointly by different specialties. How is multidisciplinary collaboration organized at the LMU Klinikum?

That's true. Visceral Surgery is probably one of the few fields in medicine that has really a lot of contacts with other fields because we work together with endocrinologists, oncologists, gastroenterologists, radiologists, and with intensive care medicine for perioperative treatment and postoperatively with rehabilitation centers. We need to interact and communicate with all these people. On the other hand, as visceral surgeons, we need to know about all these small parts by ourselves, and we need to interact with the other fields of medicine.

At the LMU, we organize it that we have conferences on each patient before we operate on him or her. (On the conferences) we not only talk about the disease, but we also talk about the comorbidities and whether we need to change the condition before we do the surgery. It's very interactive before we actually start surgery in some diseases, especially in oncological diseases, we need to treat by chemotherapy or radiochemotherapy first and then do the operation much later, so it's an interdisciplinary work and we need to be part of it from the beginning. Therefore we have a lot of tumor boards, and also boards for benign diseases.

On the other hand, every day, we have conferences in the morning about what was the night shift like. You have to interact with all the people on call, not only the surgeons. And of course, we have the board meeting where we reflect on all the patients we will operate on the next day because we need to discuss again if this is the right patient, if this is the right technique for our plan. Everybody including the anesthesiologist is part of it.

So it's a lot of work to interact. You not only need to be a good surgeon, but you also need to be a good communicator, even in the year 2022 as well, (laughs) but it's part of the job and it's fun.

6. The clinic you lead has two sites in two different campuses. The clinical team completed 3,500 in the year 2021. The scientific output of the research team is also stunning. What’s the biggest challenge when managing such a large clinic?

The biggest challenge is to get the organization running, which means you need to be sure that whatever you organize actually works because you cannot be everywhere at the same time. Things should be okay without you being there. So you need to have the right people working with you. I think that’s the main challenge, in every field, in every business. Once you think you can do everything on your own, you are lost, so you need to surround yourself with good people and then things work. You need to give them the trust and then they have the confidence to perform. Of course you work hard as a person, but you cannot do everything especially not on two sites. There's no clone you know (laughs). So this is the way it works and it's fun when you see that everything works out nicely.

7. The LMU Klinikum is one of the largest university/teaching hospitals in Europe. Every year you train lots of medical students/young surgeons at your clinic.

7.1 Do you have suggestions (to the chiefs in China) on how to train the young generation?

In China, you have even bigger hospitals so you probably train even more students (laughs), but of course, we have a challenge today and probably this is very similar in every country because the younger generation has a different idea of work-life balance than the older generation. Therefore, we need to be very attractive to the students to actually enter surgery because surgery is a very demanding field and you need to work quite a lot. There are other fields in medicine that are probably a little easier on you and where you are also capable of working halftime or even only 20% once you have reached your certified level. In surgery, we need to learn from those fields. It's difficult because nobody would buy a ticket to a concert of a violin player who trains once a week because you know probably it's not a good concert. It is the same true for surgery, which is also an art and you're performing with your hands so you need to be in training. The idea really is to reduce the learning curve by using simulation, robotics, and artificial intelligence systems.I'm not quite sure whether it's going to work, but this is at least an idea of how we will survive.

The second important point is that in Germany, medical students are mainly female - 70% of medical students in Germany are female but so far surgery does not attract too many female students. This is something we need to improve. We cannot only focus on male surgeons because that's a typical thing in Germany in the past and it changed. In my department, at the moment, we have 50% of women, but it's mainly the younger ones. And in the older generation, we do not have 50%, but only 15-20%. It is a changing of gender in the field and in the whole field of medicine. We need to come up with solutions. In Germany, we need a lot of things to help families care for their kids, for example to have kindergartens and all this so that both parents can actually work. And in surgery, as I said, we need to come up with models to actually work only half time or something like this to keep the places busy and actually to be successful. So it's a big challenge in Germany, especially for the surgical fields. I give you a number, 50% of the medical students want to become surgeons because it's very attractive and very nice but once they finish medical school, only 5% enter surgery. So we are losing a lot of students and a lot of potentials. The tip to the Chinese colleagues would be to do something different than we do (laughs).

7.2 How to keep them after they grow up to a “qualified/good” surgeon?

Okay, that's also difficult. In Germany, the system is probably different than anywhere else. After getting trained at the university, you have the option to go to a smaller hospital after you are certified and then become an attending there, or you stay at the university until you become a chief somewhere yourself, and then you have to move somewhere else. In Germany, we have very few positions where you can stay at the university in the sub-field or sub-specialty. This is something we need to develop and is actually developing over the last ten to fifteen years so that the specialists can stay at the university without being the boss or the chief who has to care about all the administrative work as well. It's changing. Around fifteen years ago, the chief was always the oldest person in the department. And because everybody was leaving the department, the gap in age was getting bigger and bigger and bigger, the longer you were there. Nowadays it changes a little bit so you have these permanent positions, but I personally feel not enough at the moment but it's changing. And this also gives everybody an opportunity to sub-specialize in the field and to keep these very good surgeons and very good co-workers in the system. And of course, you not only need to give them a position you also need to actually pay them, adequately.

7.3 What advice would you give to young surgeons?

I would, first of all, tell them it's the best field they could have chosen. It's definitely very satisfying - you have a short feedback time because you know whether you were successful or whether you failed right away. It's challenging but also rewarding. The patients really will give you a good feedback when you treat them well.

You need to work very hard to actually become a good surgeon, but then you need to kind of balance whether you want to be only a surgeon or maybe also an academic surgeon who does research. If you want to do this, you can develop and advance the field - you can develop new techniques or new approaches for treatment. To actually do this, you need to go to a big hospital or university. But no matter what your aim is, you will find a good job because good surgeons are desperately needed anywhere. So it's really a good field to enter.

8. You have a degree of Master of Business Administration in the field of healthcare. How does this experience influence you in managing a clinic?

The job of a surgeon really changed over the years. Around twenty years ago, the financial system in Germany was like this - at the end of the year, you were telling the administration that a certain amount of money of your cost and you would get some money from the county or country. Nowadays we are in a system where we are actually in competition with other hospitals and we need to work in an effective and economical way. So the MBA helped me to actually understand what the administration of my hospital was telling me and what their aim is, because they don't speak the language of someone who is a surgeon or a medical doctor, they speak the business talk and administrative talk.

Actually, I'm not a specialist in anything there, but by starting the MBA, you get the main idea, you know the wordings, and you know the ideas of how to organize and lead a hospital also from the financial way. This really helped me a lot. And it helps you to come up with the budget of your department every year, from which you need to see that your patients actually are not only treated medically in the correct way but also economically in a balanced way. It's not that we are a profitable center as a university, but we cannot give away the money like we used to do. We need to be balanced as well with regard to the costs, including the cost of all our surgeons and our devices in the operating room. And once you know how to handle this, it's very helpful.

9. As a professor, a surgeon, the chief of such a clinic, how do you balance your personal life, administration, clinical practice, research activities and lecturing?

You try to do the best every day because there's no way out and you need to balance all these different parts of your job. The administrative work, clinical work, research activities and lecturing, all these four parts are in your job description. Of course, the focus varies in the different stages of your career. In the beginning, you probably concentrate more on the clinical practice or on your research activities, then later on lecturing and then the older you become the more administrative work you gain. The main focus stays on patient care, as a surgeon. This is really important because this is what you're really doing and this is where you are rewarded most - from the patients.

Therefore, you need to differentiate the really important part of your work from those which are very important and you probably have to do yourself, or you have to at least control yourself and those which you can delegate. Otherwise, you need to work 48 hours a day which is not possible. So you need to be organized yourself, or you need to have someone who organizes you. For example, my whole secretaries organize me every day (laughs). You need to be in a system that works.

Of course, the whole workload is very high so my spare time is limited. What is true for your job is the same true for your spare time - for all the time you're outside the hospital, you need to be organized to enable yourself to do something. If you just go home and then start thinking of what you're going to do, you probably don't do anything.

10. When you were a med student, you once studied in UK and USA. Years later, you visited the Massachusetts General Hospital as a postdoc fellow before you began your clinical career. And before the pandemic, you visited China for many times, visiting hospitals and attending congresses. How important is it for a medical doctor to visit different hospitals or different countries in different stages of their career?

It's a privilege to go to other countries. This is something I learned when I was in high school when I was able to go to England, and then in medical school, I had some opportunities to go abroad into other systems. You always learn (when visiting) because you learn from the system, you learn from the people. And because every system is a little different, you can gain something from it.

As a German medical student and a surgeon, it was always good to go to the United States to see things that probably will come up in Germany about ten to fifteen years later. They always have problems there, which we will face probably ten years later, so if you go there, you can anticipate what is going to come. This is very helpful.

To go to China was very, very interesting. I have never seen such big units. I was in big hospitals in Shanghai, in Wuhan, and several other cities. I thought I have to organize a lot, but these hospitals really organize a lot. It's incredible, but of course, it's a different system so you have other possibilities to organize. But you can always get some ideas on how to advance your own working environment. It's really a privilege to go abroad and to have the chance to learn from others so I always like to do this.

To go to conferences and meetings is something that is part of the job as an academic surgeon. There are not many jobs where you can do this, that's why I would say it's good for young people to enter an academic career.

11. What is your proudest career achievement to date and why?

That's difficult, but in the career of a German medical person, the habilitation is, in my opinion, the most important part. The habilitation is a summary of five to eight different studies you have performed scientifically and you write it in a small book, and you present it in front of the university. Once you actually are accepted with that thesis, you become an assistant professor and a lecturer of surgery at the university. You have to work a long long long time for this, so in general it takes about ten years to get to that point. That's when things really start to to to work out. So it's something everybody likes to have.

This is really is a main step once you become an academic surgeon because then you normally are allowed not only to give lectures and provide teaching to students, but also to have your own scientific group. That's the start of the academic career, at least from my perspective.

12. You are the President of German Society for General and Visceral Surgery (DGAV). What does this mean to you? How important do you think professional societies like DGAV and DGVS are?

First of all, it's a great honor to be the President of that fantastic society, because we represent 6,000 surgeons. I'm also on the board of directors of the German Society of Surgery, where we represent 25,000 surgeons of Germany.

This is also a big responsibility because you need to politically use the power of these societies to influence our working conditions. For example, one of the big topics at the moment in Germany is that many hospitals will have a deficit at the end of the year because it's very difficult to have the finances for the treatment of patients at the moment. Surgical cases are being paid, but, for example, new technical methods are not balanced into the system. For example, if you use a robot, you won't get money for using the robot. If you want to change the treatment, you need to get the acceptance of new methods. Things like this need to be addressed to the politics by the societies.

And also, other topics this year are minimum volume of centralization, networking, etc., which are very important because a lot of hospitals at the moment perform surgical cases, although they may only do five or ten cases a year then the quality is not good enough. But then you need to come up with a system that these hospitals get a certain task to do because otherwise they won't survive and we need to close them, which might be a solution. Things like this need to be addressed by the societies and that's not only true for the surgical societies, but also for the DGVS which is our partner society of gastroenterology.

And we also have to guarantee the teaching quality of the residents and the surgeons in training all over Germany not only in our own department. We probably need to come up with some new methods for education of surgeons. For example, DGAV, the German Society for General and Visceral Surgery, has developed an online tool for education for surgeons and we also give a lot of courses.

That’s the job of the President who advocates and gives this kind of information to the public.

13. The COVID-19 pandemic is one of the biggest challenges facing modern healthcare. What impact do you see this having on the field of general and visceral surgery?

The impact is huge. Over the last three years, the government had to support the hospitals, otherwise, they had a huge deficit just to compensate for all the extra amount of costs. But this is going to probably be stopped next year, so all the hospitals need to be able to finance themselves again on their own. That means that once the support is not there anymore, a lot of hospitals will have a problem surviving. That's going to be a big challenge, and we will see next year or the year after.

With regard to general surgery, we had a big dip in surgical cases at the beginning of the pandemic in 2020, because we needed all the nurses and all the doctors not to work in the operating room, but in the intensive care units. But now we have a vaccination rate of about 80% in Germany. And 95% of old people had either been infected or are vaccinated. There are only 5% who didn't have any contact with the virus. So we are safe and we can go back to more or less normal life. Visceral surgery can do the normal job again everywhere. We will see what will happen when the winter comes but I don't expect anything really bad.

The only long-term impact really is what will happen to the medical systems and the hospitals in Germany. It's probably not affecting the big hospitals and not the universities, but the smaller hospitals.

14. Despite all other roles, what’s the most fascinating part of your profession as a medical doctor? And what would you have been if you had not been a medical doctor?

I've never thought of an alternative so that's an easy answer. I always wanted to become a medical doctor and I was lucky enough to get support at the university in advance.

The most fascinating part of it, I think, is to help with your own hands. And the other thing is to teach students. You can actually work with younger people, which really helps. It's fascinating.

15. What are your hobbies during your leisure time?

There is almost no time for it, but, I have some hobbies. I do sports and I try to keep fit, not as much as I used to, it's getting less and less. I play the jazz guitar and of course as everybody, read books, listen to music, enjoy life.